Child friendly places are the future

Tibbalds

Ten years ago I moved to London and quickly became accustomed to squeezing my way through throngs of people to get around on the tube and buses. Later, squeezing my way through traffic and exhaust fumes on my bicycle become part of my everyday. But then, 3 years ago, everything changed, and I experienced London anew, as a parent with a pram. Although London offered many things to explore with a young child, I also came up against many barriers and issues I hadn’t noticed before. Getting around was no longer as quick, easy and safe as before and the reports about London’s poor air quality became a bigger concern for me. As an urban designer, the experience opened my eyes to the massive opportunities to improve the city for everybody by making it better for all those that need extra care, support and nurture in their daily lives, especially the very young who are just starting their lives.

Earlier this year, an invitation to an urban design event asked me “If you could experience the city from 95cm, the height of a 3-year-old, what would you change?” I had a lot of ideas of what I would change to make places more child friendly so I headed off with my now 3-year-old son on the back of my bicycle to ARUP’s London headquarters to take part in a LEGO workshop together. The corporate quiet of ARUPs headquarters was transformed by lively children of all ages arriving for the workshop.

Over the last few years there has been growing interest, initiatives and funding to make cities more innovative, more resilient, more sustainable and healthier, for example the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities, the Bloomberg Mayors Innovation Challenge, the NHS Healthy New Towns Programme and the GLA’s Living Streets. But more recently the focus is shifting, even within some of these initiatives, towards the needs of children in cities, because the very young are the most affected now – and over the rest of their lives – by how we plan, improve and build places.

This shift is being driven, in part, by a growing body of very worrying scientific evidence on the potential long-term detrimental effects of urban environments on the very young, not to mention the long-term costs to society. Without becoming too bogged down in detail, one particularly important issue is air pollution, which limits the development of a child’s lung capacity and increases the number of those growing up with lung problems and asthma. In London, this issue has been highlighted in the news by the death in 2013 of nine year old Ella Kissi-Debrah in south London. This is now making news headlines as a new inquest into her death is being requested given the association found between her emergency hospital admissions and spikes in levels of air pollution.

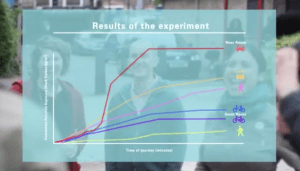

There have been a growing number of air pollution studies in London, some of which have shown that air pollution levels around some schools are also too high. One particularly insightful small experiment I came across demonstrated that those getting around London in cars are exposed to higher levels of air pollution than those walking, cycling or taking a bus.

Back at the Lego workshop, the children were given the ambitious challenge of building a city where children and parents can play everywhere, using a huge mound of Lego and a 30x30cm base plate. My son immediately started to play with some cars and animals he found in the Lego mound, as did many children of a similar age. Then he found Lego railway bridge parts that he repurposed as slides for animals and together we created a double-sided slide between two pyramids, combining play, imagination and built form, something not far from the idea behind the new waste incinerator with its own (snowless) ski slope in Copenhagen which has just been completed.

The imaginative Lego creations by children of all ages at the workshop addressed the city challenges in different and unexpected ways. Many involved animals and trees, which happened to be abundant in the mounds of Lego. There was an idea to replace cars with horses and a thoughtful suggestion to breathe life back into derelict spaces through play.

After all the children received their Lego city building certificates and went home to bed, the proposals were put on display for the evening grown-ups event. It was introduced by the chairman of ARUP and the CEO of the Bernard van Leer Foundation, a Dutch organisation focusing on improving early childhood development. The discussion panel included UNICEF, Lego, British Land, the GLA and NACTO (National Association of City Transportation Officials).

Each organisation presented their distinct goals, tools and diverse approaches to child friendly cities including the GLA’s health streets toolbox, NACTO’s Urban Street Design Guide and the experience attracting families to new spaces in Kings Cross, to mention a few. But there was unanimous consensus amongst the speakers that addressing the needs of children and their carers makes places more successful from an economic, social and environmental standpoint.

Yet even in the “garden cities”, “healthy towns” and “eco developments” of today, the focus is still on cars, numbers of homes and the economy rather than quality of life, health and the environment. By concentrating minds and investment on places that are better for children we can achieve a shift and make places and spaces that are better for everyone, including developers, without adversely affecting the long-term health and life chances of the next generation. Because creating child friendly places does not just create better places for everyone, it also provides the foundations for a friendlier future.

Topics:

Related Updates

Lizzie Le Mare speaking at the Housing Finance Conference 2025

Tibbalds

Lizzie Le Mare joins NLA Expert Panel

Tibbalds

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.