CIL – A tool for capturing social value or mitigating poor development?

Tibbalds

Tibbalds’ Planning Assistant Lizzie Bundred-Woodward who is currently studying for a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning at the University of Westminster discusses the current arrangements around the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) and considers both the problems it raises and possible ways forward for the charge.

I’m sure I’m not alone amongst colleagues in ranking calculating Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) contributions low on the list of interesting things to do. I specifically chose planning for the perceived lack of necessary mathematical ability. Jokes aside, there is dissatisfaction with the current CIL system within both the public and private sector. A review, culminating in the Housing White Paper ‘Fixing our broken housing market’ (February 2017)1 found the system to be slow and not as ‘simple, transparent or certain as originally intended.’ Hopes in March that CIL reform was imminent alongside the draft NPPF were dashed when the NPPF was adopted in July. The predominant issues arising, aside from my mathematical capabilities, are many and varied.

Indexation

The first is indexation. The current method using the BICS all-in-tender price index, secures councils a fairer levy, but is too convoluted a process for both developers and councils to utilise. Further, access is costly, placing an additional financial burden on both parties. Calls for the use of a market responsive indexation rate, based on regional house prices, have thus far been ignored. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Inconsistent and complex coverage

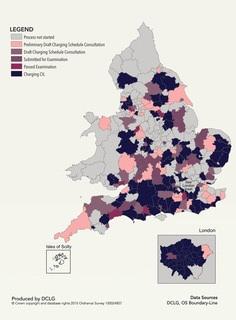

‘The Value, Impact and Delivery of The Community Infrastructure Levy’ (Three Dragons & University of Reading, February 2017) examined CIL implementation across England. It found that local authorities adopting charging schedules have been concentrated within the more affluent parts of the country where market and land values are higher, with over 50% in London and the South East. This is clearly not the ‘blanket approach’ of infrastructure funding the Government envisioned in 2010. Instead, we have a fragmented mix of CIL and non-CIL charging authorities and a continuing heavy reliance on complex s106 Agreements. Local authorities cited various reasons for non-adoption including: delays to Local Plan adoption, difficulties in identifying necessary infrastructure (inconsistent use of Regulation 123 lists), complications in managing CIL together with S106, viability concerns and a dearth of employees and financial resources.

For areas with adopted charging schedules, delivery was found to be slower than anticipated. Problems with s106 pooling restrictions and issues with long term phasing have led to delays and cancellations of necessary major infrastructure projects due to lack of ‘joined-up funding’. The long, variable list of exemptions and the need to allocate CIL for adopted Neighbourhood Plan areas has created additional work for authorities. There have also been concerns that Neighbourhood Forums and Parish Councils may not be equipped with the necessary skills, knowledge and time to implement projects once funding has been secured.

Pressure on affordable housing

Pressure to increase affordable housing has also brought criticism of CIL. There remains an expectation when negotiating s106 agreements that other contributions, including CIL, should be considered. Developers argue that the levy is an additional financial burden, reducing the overall contribution to affordable housing on viability grounds. Data from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government shows that an estimated £5.1bn was agreed through s106 in 2016/17, of which £4bn was used for affordable housing, equating to around 50,000 new homes. In contrast only £0.9bn of CIL was levied in the same period and did not contribute to any new housing.

If the Government is keen for a simpler approach to planning contributions and viability, it seems wholly illogical that councils cannot use CIL funding towards social housing provision given the universal need for more affordable homes; housing is seemingly why s106 remains so prevalent. How this would work in practice requires testing, though a good starting place could be to allocate a percentage of CIL to social rented housing nationally.

Affordable housing exemptions have certainly been a positive factor in encouraging housing development. However, ambiguous definitions of what constitutes ‘affordable housing’ has led to a variety of tenures coming forward (particularly intermediate products) which will be more viable than housing at social rent levels. A clearer definition from Government would be useful to incentivise housebuilders to provide more affordable products.

Community involvement

At Planning Committee we’ve commonly found that members are keen to secure items for developer contributions though there are no mechanisms to secure CIL for a particular project. Once CIL is secured, there is an absence in reporting where it is actually spent. This summer for the first time, Reading Borough Council consulted on where their allocated £1m for local projects (15% of total CIL collection) should be spent. This should be a requirement for all authorities when allocating local CIL funding. Engaging local communities in the allocation process will engender a greater sense of ownership of their area and may appease certain members of the community more opposed to development if they can see they are truly getting something out of it.

Mayoral CIL (MCIL)

Despite the shortcomings of CIL, Mayoral CIL (MCIL) has been successfully used by the Mayor of London to fund the construction of Crossrail (estimated £600m of developer contributions)2. Though the appetite for development may be greater in London, and hence CIL more feasible, the major factor in the success of MCIL has been the ‘flat rate’ set across zones and uses, with no confusing exemptions (apart from affordable housing). This has meant that the process of calculating and collecting has been relatively straightforward (notwithstanding indexation). MCIL has also succeeded because the specific infrastructure requirement (Crossrail) was established from the start, meaning that contributions have been completely transparent, a major shortcoming of CIL.

It is anticipated that the new Metro Mayors3 will be given devolved powers to utilise MCIL (or similar) for regional strategic infrastructure investment, which will work across planning authority boundaries eliminating problems with local political differences. This approach seems more optimistic and will hopefully help rejuvenate areas that have been neglected and suffered under austerity and potentially produce a more coherent approach particularly outside the south east. However, this remains to be realised and will take time and co-operation between local authorities to identify need.

In terms of Government commitments for reform, recommendations for a new twin-tracked system of strategic and local tariffs are yet to be thoroughly reviewed and there are continued concerns that this may not help with the complexities of viability assessments. There is also no obvious strategy for how to assist non-adopters or authorities where the system has demonstrably failed to secure sufficient contributions. These areas in the future may be assisted through regional tariffs.

So, in the meantime, CIL remains as confusing as ever.

- 1CIL_Research_report.pdf

- 2Crossrail – Funding

- 3 For the Combined Authorities of Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, Greater Manchester, Liverpool City Region, Tees Valley, West of England and the West Midlands.

Topics:

Related Updates

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.