Exploring Creative Ideas around Urban Problems

Kieran Easton, Planning Assistant at Tibbalds, explores new creative ideas around urban problems at a recent Hackathon and reflects on the experience.

It seems that for many people, including myself, the lockdown of 2020 reignited the love of cycling. The restrictions to our daily lives meant that within our allotted time, a bike offered the chance to unlock unexplored corners of our local areas, fulfil our exercise quota, and enjoy roads with less cars than ever. The experience was enhanced by the introduction of numerous temporary cycle lanes and Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, and the demand was evidenced by six-month waits for new bikes in shops.

During the pandemic, I spent two days taking part in a 48hr ‘Hackathon’ organised by the Bartlett, at UCL. A friend, who was studying a masters at the time, invited a few of us to take part. Any student could put together a team, and in total there were around 40 teams registered. The event, which runs annually, seemed more topical than ever, as the pandemic brought into focus the issues and inequalities that come with dense urban living. In a slight tangent from my day-to-day project work, the opportunity gave teams a chance to think about creative solutions to an array of urban problems.

In my team of three, we worked with mentors to develop our response to a chosen urban problem. We could cover any topic under categories such as transport, energy, health and wellbeing, food systems and supply chains, and urbanisation etc. Solutions did not have to specifically respond directly to the pandemic, though most teams did use this as a focus.

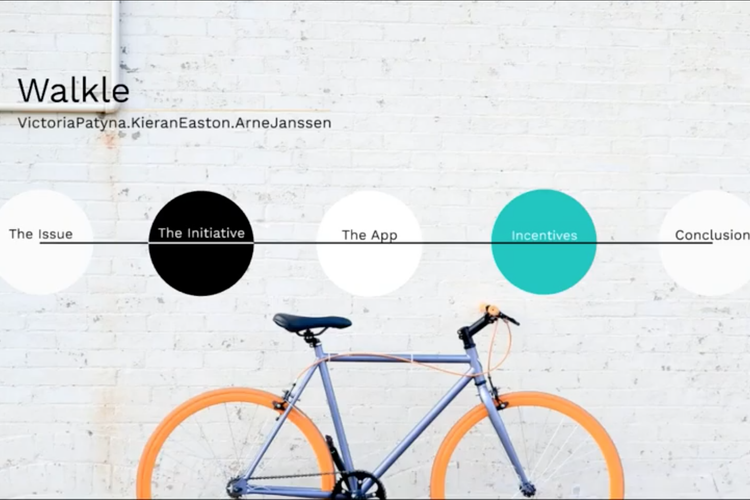

We chose to identify a solution to a problem under the transport and travel thread, and we then had two days to produce a video, presentation, document, or poster, identifying the problem being solved, our proposed solution, and how it will change the world (simple right?). Among our team, we debated everything from drones, to autonomous vehicles, to flying taxis. But we settled quickly on the need to improve uptake in walking and cycling as active modes of transport.

Our solution was an app, Walkle, based on rewarding local communities for utilising more sustainable modes of transport by providing better infrastructure to facilitate said sustainable modes of transport. This was based on research that we undertook looking at the barriers - both perceived and actual - that prevented people from cycling and walking. One of the strongest deterrents to cycling was the perceived safety issues. Results from the studies indicated that cycle infrastructure such as segregated cycle lanes and secure cycle storage facilities would increase participation in cycling.

It should be reiterated that this solution was developed over 48 hours, and there are shortfalls and improvements to be made. The app is ambitious and the issue of receiving funding and the intersection with government will always be significant hurdles. The specific branch of the EU Emissions Trading System that we referenced was terminated at the end of 2020, and coupled with Brexit, this funding avenue looks increasingly unlikely.

We had to think carefully about encouraging behavioural change through an incentive method, without discriminating against or disadvantaging people who couldn't change their mode of transport for whatever reason. As a result, we didn't propose any sanctions for car drivers, but instead offered incentives to cycle more - new cycle lanes, improved cycle storage etc. It also became quickly apparent that it wasn't reasonable to allow boroughs to compete for funding, as some already have markedly better infrastructure/more people cycling (particularly where top-down incentives have already been put in place e.g. the ‘Mini-Holland programme’ in Walthamstow). Therefore, through the model proposed in Walkle, the app would automatically set individual benchmarks and measure improvement against this, hopefully making the process more equitable.

Whilst it is not a polished model, it does raise interesting questions about changing people’s behaviour and the methods of delivering active travel infrastructure - placing the choice in the hands of the community. After all, if the decision-making power was given to the people who use it, how would this change the built environment around us? This feedback loop could improve the situation exponentially; as more people walk and cycle, the tangible improvements to local areas become more evident thus further encouraging more (and sustained) behavioural change. An app-based platform is accessible, cheap, adaptive, and offers flexibility to the owners and users.

Unfortunately, we did not win. But interestingly enough the three winners all followed the transport and travel thread and all their solutions involved cycling. One project encouraged greater participation of women in cycling, one covered cargo bikes, and one looked at engaging local communities in cycle infrastructure construction. The winners were then invited to collaborate further with the university and discuss their ideas. The other submissions can be found here.

Far more must be done to address the causes of the climate emergency and whilst Walkle was an idea formulated over just a few days, it is essential (and exciting) to continue to think about these ideas and develop concepts that will help solve these urban problems.

Related Updates

Marlcombe, East Devon selected as one of the New Towns

Tibbalds

Lizzie Le Mare attending LREF 2025

Tibbalds

Newham Council’s 50% affordable Carpenters Estate regeneration gets underway

Tibbalds

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.