Placemaking and the 15 Minute City: a solution to more community-orientated, greener, and equitable neighbourhoods?

Kieran Easton, Planner and Assistant Urban Designer at Tibbalds, explores the theme of the 15-minute city.

As part of my Urban Design Masters course, we were invited to explore the theme of the 15-minute City, and its implications for, and relevance to, enhanced placemaking. Using examples from around the world, and anticipating the application of the concept in Paris, this piece explores the opportunities and challenges around the implementation of the concept at various scales.

Cities worldwide are facing an unprecedented level of scrutiny in their response to a series of escalating urban issues, for example: the climate crisis; the housing (unaffordability) crisis; and the air quality crisis, all whilst managing the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK, and many other countries across the world have employed a “Green Recovery” strategy in the form of a variety of policy adjustments and fiscal stimuli to cut CO2 emissions and boost economies post-pandemic. The “15-minute City” (FMC) concept has gained traction as one such spatial model that could help enable a Green Recovery, as well as facilitate wider social, environmental, and placemaking benefits.

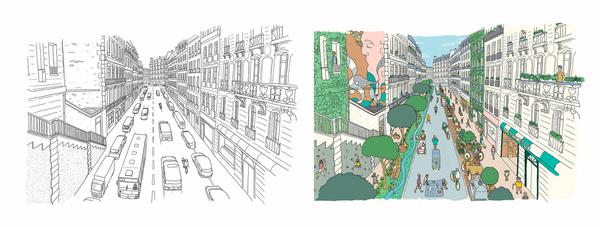

Though the specific concept of a FMC was first coined in 2016, interest in the model has accelerated since the pandemic, when daily life and activities were restricted to those which could be undertaken and reached within the local neighbourhood (note: though the FMC is specific, the concept has been around for longer - first identified in Portland, Oregon). These restrictions, and a brief emphasis on “local”, brought into sharp reality the amount of time spent travelling to work, the lack of amenities at a local level, and the overwhelming “busyness” that came with traditional urban life. Developed by Professor Carlos Moreno, in FMCs, all residents should be able to meet their daily needs within a short 15-minute walk or cycle. Moreno argues that cities should be re-designed around human-sized spaces, so residents can easily access work, housing, food, health, education, culture and leisure. The four guiding principles are: Ecology; Proximity; Solidarity; and Participation. In Paris, Mayor Hidalgo is the first to implement the FMC as part of the “Paris En Commun” strategy, where the concept will manifest in a series of interventions, including: better, safer bike and pedestrian routes; giving public and semi-public spaces multiple uses; introducing “citizen kiosks”; and strengthening local shop networks to promote local food production.

Illustrative interpretation of what the ‘Paris En Commun’ interventions could look like in Paris. Illustrations by N.Bascop for Paris En Commun

In my opinion, the concept and principles of the FMC are of paramount importance and relevance in current debates; and not only does this concept have the ability to act as a vehicle to deliver better placemaking, but the principles also align with the need to reduce travel distances, re-introduce nature back into urban areas, and encourage new behavioural patterns to help tackle the urgent climate crisis. The FMC concept packages a lot of the principles that we know now to be best practice (and have been successfully applied over recent decades): walkability and permeability; urban greening; density; co-location of uses, into a robust vision that can be held up to encourage buy-in from stakeholders and local communities. The vision is strong, and it is difficult to dispute the underlying principles, however, only in the implementation and tangible actions can the true value to placemaking (and the environment) be assessed.

On paper, the principles of the FMCs (ecology, solidarity, proximity, and participation) very closely align with the core themes of placemaking. Given that the FMC concept, as proposed by Moreno, has not yet been fully realised, it is necessary to appraise similar concepts which have had real-world application. In 2012, Portland City Council published its “Portland Plan”, which included the concept of a 20-minute neighbourhood (also named a “complete neighbourhood”), where residents could access the goods and services required by daily life: including healthy food, parks and green space, schools, commercial activities and businesses, within 20 minutes. The Portland Plan set an ambitious target of 80% of Portlanders to live in complete neighbourhoods by 2035 (increased to 90% during the pandemic), which provides an index to measure the application of FMCs, but not necessarily the success.

Similarly, in Melbourne “20-minute neighbourhoods” aim to ensure that most everyday needs can be met within a 20-minute walk, cycle or local public transport trip, as outlined in Plan Melbourne 2017-2050. Interventions include new neighbourhood cores, full pedestrianisation of areas, new green areas, the use of schoolyards for sport, community landscaping and local food production, which all aim to increase social interaction and participation. Engagement with the local communities and their involvement in co-design practices in the three pilot areas in Melbourne has been commended in literature (notably Pozoukidou and Chatziyiannaki, 2021), and further guidance has been released to focus on the successful implementation in outer-suburb Greenfield locations (released by Resilient Melbourne). There is also evidence to suggest that Paris’ implementation of the FMC could be successfully participatory for local communities, and 5% of the Paris En Commun budget has been allocated to encourage citizen participation in co-design and the application of the FMC principles. Whether this does truly facilitate enhanced (and more equitable) engagement and co-design in Paris will remain to be seen, but it will be hoped that an emphasis on local interventions within people’s immediate proximity, and the fact that people are spending more time in their neighbourhood, should mean residents are more likely to want to (and have greater opportunity to) have a stake in the change. The Melbourne Plan, and Portland Plan, therefore both seek to improve the principles of placemaking, and early signs are promising, but further empirical studies will need to be undertaken in due course to understand this change.

Melbourne’s “20-Minute Neighbourhoods”. Image from Plan Melbourne 2017 - 2050: 20-minute neighbourhoods, State Government of Victoria.

There are however significant barriers to the application of the concept, and many reasons why traditional centres have already become detached from the principles of the FMC. The emphasis on proximity and locality contrasts against much of the rhetoric of economic development of recent years, which was led by the market, and includes the centralisation of facilities and services which in many places were once found in close proximity to people’s neighbourhoods. For example, in the UK, post-offices, pubs, health facilities, and grocers which were once found on the high street, have been subsumed or centralised as high streets have struggled to maintain relevance in a world of online shopping, large corporations, and delivery culture. There are a number of political, financial, and regulatory barriers to the FMC model, and there will need to be largescale reform and behavioural change to realise its full potential. The existing planning system for example, is very restrictive in its land uses, and there will need to be greater collaboration and deregulation to enable more flexible use of existing spaces (whilst noting that the newly introduced “Use Class E” does begin to introduce this flexibility which will assist high-streets).

There may be unintentional consequences of the FMC model that may only become apparent once the concept has been applied in more locations, and been established for longer. Successful placemaking can only be achieved if it is equitable, and benefits everyone. Yet, the Paris En Commun strategy is only being applied to the inner ring area of the city, mainly inhabited by wealthier Parisians, and not to the Banlieus; and there is thus concern the FMC could further reinforce social disparities across the city. There is also concern that the FMC concept could further facilitate gentrification; as FMC neighbourhoods acquire more local facilities, making them more desirable, and thus likely increasing house prices and potentially causing displacement of established communities. In Melbourne they have countered this by arguing that the concept is a whole “city-wide” vision, and therefore all inhabitants will benefit and prosper. A core criterion for valuable placemaking is that there must be greater citizen control and participation. In particular, the process must be inclusive to low-income and marginalised communities, with an emphasis on intersectionality, to achieve true representational placemaking. There is not currently enough details in the FMC model to ensure this intersectional participation, or the ability to monitor this, and thus the status quo risks these groups continuing to be under-represented in these processes.

It should be recognised that there is unlikely to ever be a fully complete “15-minute city”. Ensuring all inhabitants can reach most of their essential services within 15 minutes is extraordinarily ambitious; and the challenges of implementation of the concept will be significant (and insurmountable in some places). Challenges will vary depending on location (but will include spatial, political, systemic/regulatory, and financial), as cities are also implementing the concept from very different starting positions. But what is important, is that the principles of the FMC are applied in such a way that deliver better placemaking, for everyone, no matter whether a smaller peri-urban location, a dense historic European city core, or a city in the Global South. This essay has highlighted the parallels between the FMC, and placemaking, and has explained the significant opportunities for the FMC to advance place quality whilst facilitating a Green Recovery. The application of the concept must be done faithfully, and further details will be required regarding addressing housing affordability, community participation, and equitable access to public services, and further investigation will need to be done to evaluate the long-term implications of the model and placemaking success.

Related Updates

A step in the right direction

Tibbalds

Medium density housing – how to deliver greater choice

Tibbalds

Lizzie Le Mare discusses the planning System in HE article

Tibbalds

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.