Play Streets

Tibbalds

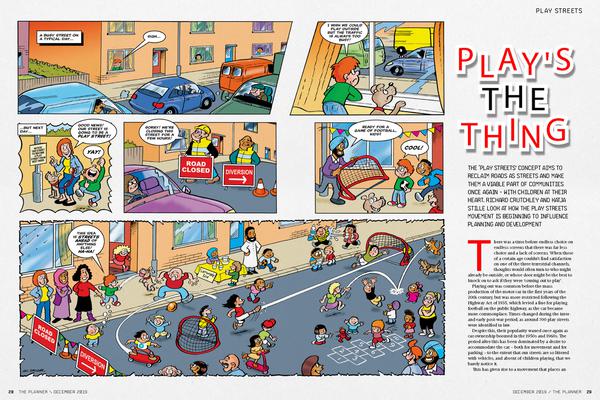

I’ve been involved in running a play street for several years, and have had experience of other play streets across London and elsewhere. Combined with my role at Tibbalds, and a desire to see more people friendly places in both existing and new development, the chance to promote the idea of play as one aspect of a healthy street environment was too good to miss.When it came to illustrating the piece for The Planner, they had the idea of a comic strip approach to reflect the focus on kids and young people, whilst playing on the nostalgia that both comics and playing in the street bring to today’s middle-aged parents. Lew Stringer’s work spans just about every major comic of the past 40 years, alongside other publications, promotions and commissions. His artwork for The Planner stands out with its colour, humour and detailing whilst also capturing the essence of the street play idea in a handful of clever panels. It was a thrill to see our words appearing alongside this super illustration!

Play's the Thing

The ‘Play Streets’ concept aims to reclaim roads as streets and make them a viable part of communities once again – with children at their heart. Richard Crutchley and Katja Stille look at how the play streets movement is beginning to influence planning and development

There was a time before endless choice on endless screens that there was far less choice and a lack of screens. When those of a certain age couldn’t find satisfaction on one of the three terrestrial channels, thoughts would often turn to who might already be outside, or whose door might be the best to knock on to ask if they were ‘coming out to play’.

Playing out was common before the mass production of the motor car in the first years of the 20th century, but was more restricted following the Highway Act of 1935, which levied a fine for playing football on the public highway, as the car became more commonplace. Times changed during the inter- and early post-war period, as around 700 play streets were identified in law.

Despite this, their popularity waned once again as car ownership boomed in the 1950s and 1960s. The period after this has been dominated by a desire to accommodate the car – both for movement and for parking – to the extent that our streets are so littered with vehicles, and absent of children playing, that we barely notice it.

This has given rise to a movement that places an emphasis on reintroducing play opportunities into our streets, and actively accommodating informal play into new housing development.

The contemporary street play movement was born in Bristol in 2007, although community events to ‘take back the road’ have been going on for some time, endorsed and encouraged by the likes of the now defunct government agency, CABE.

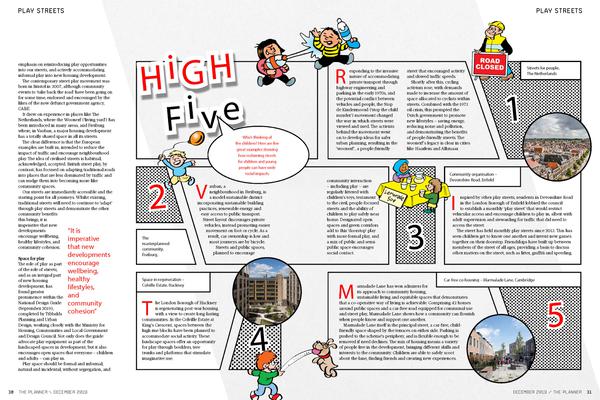

It drew on experience in places like The Netherlands, where the Woonerf (‘living yard’) has been introduced in many areas, and Freiburg where, in Vauban, a major housing development has a totally shared space in all its streets.

The clear difference is that the European examples are built in, intended to reduce the impact of traffic and encourage neighbourhood play. The idea of civilised streets is habitual, acknowledged, accepted. British street play, by contrast, has focused on adapting traditional roads into places that are less dominated by traffic and can nudge them into becoming more like community spaces.

Our streets are immediately accessible and the starting point for all journeys. Whilst existing, traditional streets will need to continue to ‘adapt’ through play streets and demonstrate the other community benefits

this brings, it is imperative that new developments encourage wellbeing, healthy lifestyles, and community cohesion.

"It is imperative that new developments encourage wellbeing, healthy lifestyles, and community cohesion”

Space for play

The role of play as part of the role of streets, and as an integral part of new housing development, has found greater prominence within the National Design Guide (September 2019), completed by Tibbalds Planning and Urban

Design, working closely with the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government and Design Council. Not only does the guide advocate play equipment as part of the landscaped spaces in development, but it also encourages open spaces that everyone – children and adults – can play in.

Play space should be formal and informal, natural and incidental, without segregation, and integrated into the very character of the development. It advocates public spaces and streets as places where play can exist, particularly in the idea of ‘doorstep play’, encouraging younger people to experience the outdoors close to their homes and in their community through free play.

This can – and should – be applied to new development, where the opportunity to integrate these activities may be more straightforward. Playing in the street needs to be considered more widely as part of any development scheme that features streets and spaces, and by all built environment professionals.

Sometimes this approach is outlined at policy level. Within recent design guides in Runnymede and Bradford, Tibbalds has been keen to advocate the importance of the play element within new development, both formal and informal and in streets and in spaces, to ensure that both officers and members have the needs of the whole community – and especially young people – at heart.

Recently, the Urban Design Group, a UK-based charity focused on raising standards of urban design, ran a conference around people-friendly places and drew out the importance of addressing the needs of children. Not only is the freedom of a child to roam undermined by the places we build, but children are less able to judge the dangers within the built environment, particularly from traffic using roads.

Children have exactly the same rights as adults to use our spaces and streets, but we are guilty of neglecting their needs as people in our approaches to the impacts of noise, pollution, traffic, activity

Children have exactly the same rights as adults to use our spaces and streets, but we are guilty of neglecting their needs as people in our approaches to the impacts of noise, pollution, traffic, activity and security. Children need play for their physical and emotional development and their social learning. This is protected within the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

But the industry doesn’t need to wait for formal guidance to make a difference. Putting them at the forefront of our design thinking now will inevitably create a better, more inclusive and healthier place for everyone.

Original article in the December 2019 issue of The Planner magazine.

Related Updates

Lizzie Le Mare speaking at the Housing Finance Conference 2025

Tibbalds

Lizzie Le Mare joins NLA Expert Panel

Tibbalds

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.