VeloCity: How we used networks and influenced change

Last week, VeloCity, a consortium made up entirely of women, won a national competition run by the National Infrastructure Commission to come up with a fresh new idea for the regeneration of land in the Cambridge-Oxford corridor.

As the industry continues on its quest to increase diversity and celebrate the role that women play in the development of our towns and cities, Jennifer Ross, director at Tibbalds Planning and Urban Design, reveals how a women’s networking event brought the team together and how they came up with the winning idea.

The VeloCity team met on pedElle, a yearly, long-distance charity cycle ride for women in the property industry organised by Club Peloton.

We had all talked a lot about what we do and why we do it as we spent many hours on the road together, passing through towns and villages across Europe.

What was clear was that we all shared a passion for placemaking and were interested in the interplay of the economic, social, environmental and spatial issues that go into making great places. And, indeed, those factors that contribute to making places that do not work quite so well.

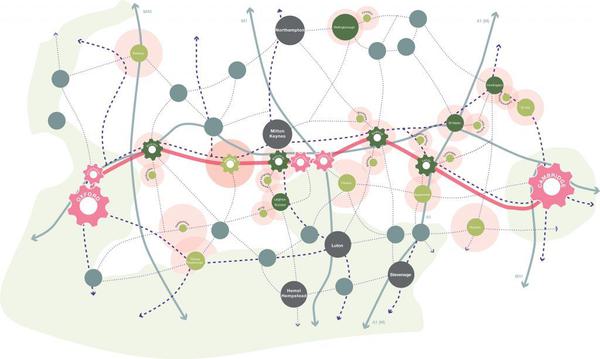

In June 2017, the NIC launched a competition to seek visionary ideas for development typologies across the corridor encompassing Cambridge, Milton Keynes, Oxford and Northampton that could contribute to delivering new homes, integrate the delivery of infrastructure and maintain the environmental and cultural character of the area.

The competition wanted to attract broad multi-disciplinary teams of urban designers, architects, planning policy and community specialists, engineers and people with good ideas to unlock housing sites, improve land supply and deliver sensitively designed new communities.

We thought this was a perfect opportunity for us to put the many hours of talking into action. We also liked the idea of creating a women-only team and exploring how we might all work together.

Over a week – with most of us on holiday – we put together our initial pitch for the submission. We wanted from the outset to look at things a bit differently and to imagine what life might be like in 2050, the time horizon of the project.

Starting with the opportunities that could be created by putting in fast efficient public infrastructure, we started to imagine a place where vehicles no longer dominate our lives, where our relationship with car ownership would change and how technology might influence such changes.

We focused on the opportunities that could be created as a result of a shift towards more integrated and finer grained public transport networks comprising rail, bus and bicycle and a reduction in the dominance of the vehicle. Such thinking started to allow us to explore different design solutions.

At the same time, we were reading a lot about the demise of the village, loss of character and identity, ageing populations, lack of affordability and dormitory places and yet we recognised that such villages formed some of the more characterful places across the corridor. In addition, we were interested in the social aspects of placemaking and issues of obesity, mental health, ageing and loneliness.

All of these factors together started to shape our idea to reimagine villages in the 21st century and how we might plan for their future sustainability and development.

We advanced Velocity, a symbiotic groupings of well-designed and balanced village communities centred around new and existing stations and supported by the necessary social, environmental economic infrastructure to allow them to function in a sustainable fashion.

We were one of 58 submissions and four shortlisted to go onto the second stage. At this second stage, Bridget Rosewell, commissioner of the NIC and competition jury said: “We will be looking for proposals that are rooted in their context and understand the local character, environment and landscape. We have asked competitors to consider how places will be integrated with infrastructure, but above all, we want to see what the proposals will mean for the lives of the people living and working in the corridor.”

So we got our maps out and got on our bikes to find a location upon which we could develop our ideas. We selected six villages around one of the new stations on the Oxford and Cambridge Corridor and spent a bit of time getting to know the location and talking to the people who lived there.

We worked together over an intensive five-week period in the evenings and at weekends evolving and brainstorming our thoughts and ideas. We were also helped by our own in-house teams, academics and through a panel of “critical friends” that we invited to participate in the process including Joanna Averley, Harriet Bourne, Mel Dodd, Hilary Satchwell and Jane Wernick.

It was amazing how much support we got in the process. When people heard our story, how we met and what we were trying to do they all offered help.

The resulting proposal seeks to turn traditional planning policy on its head in order to stimulate sustainable, finely networked places to live and work in the countryside that also connect back to main rail stations. The approach is the antithesis of the “big bang” projects that dominate political thinking, delivering within narrow remits.

The proposal prioritises cycling over vehicular transport, not because we are obsessed but because it is cost-effective, good for health and does not discriminate against those who cannot afford to drive. It addresses issues around existing villages and rural settlements – places that have a strong sense of identity but diminished community. We sought to restore them by setting a framework for them to become multi-generational, supported by a strong network of local shops, schools and health facilities.

To do this we proposed making the centre of villages denser to support more diverse and renewed community life and prevent the gradual extension of villages on either side of the road making them into corridors. We offered alternatives for deliveries and day-to-day transport and then gradually planned to displace cars by offering better alternatives. It’s an approach that values a sharing economy with collective benefits.

The approach is incremental and carefully honed, one that genuinely delivers a circular economy with a low carbon footprint. One where life moves from the high velocity of the new train and hard infrastructure and connects to the slower pace of everyday life within reimagined village communities.

The experience for us all has been revelatory and exposes how effectively and efficiently an experienced and dynamic professional team can collectively draw on each other’s skills. We have discovered that as a group of women we are mutually supportive and pull each other to new areas of focus that widen our overall sphere of interest. When one tires the others take over, just as we did on our bikes – a sort of intellectual relay.

So what have we learnt? Firstly, that informal associations of professionals can be highly effective, creative and mutually supportive. Also, that joint challenges really do develop trust and, in association with the wider network of cycling women (and men), we hope to use this initial success to continue to generate further new ideas and thinking.

Related Updates

Lizzie Le Mare joins NLA Expert Panel

Tibbalds

Lizzie Le Mare attending LREF 2024

Tibbalds

Stay In Touch

Sign up to our Newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates about making people friendly places.